Every time we code something, we create new instances. We literally use word “new” all the time. That creates a concrete object for us. It is bound to a particular type, and we can’t change it after we created it. Every time you use “new” – you create “concrete” instance. This is opposite to what good OOP principle tells us – program to interface, not implementation. Even though in this instance it almost seems too much to oblige with this concept, it is still possible. We have a way of creating objects without being bound to a concreteness of a certain type. We should use something called Factory Method.

Let’s think of an example to use. We need to have a situation where we have several different objects that we need to create, and all of them are of the same super type. Let’s take a super type Dessert. There is quite a variety of those out there: cakes, candies, lollipops… the list is endless. How can we create one of those concrete objects without using “new” operator? How about we try to hide, or encapsulate, this whole operation in a separate function of a separate class. Don’t get me wrong, we are still going to use operator “new” to instantiate an object, but now the instantiation will be delegated to an outside object, and will be decided on during runtime. The class that we moved all of this creation process is what is called Factory – it encapsulates the object creation for us. And now what we have to do is only to create instance of our factory class, and call its makeDessert() method.

What we have achieved here is a Simple Factory.

However in order to achieve greater flexibility, and ensure that all types of Dessert are possible (whether just baked desserts or ice cold ones) we need to create a structure in which subclasses, particular implementations will decide on what kind of dessert to create. We can do that by declaring Dessert class abstract, and creating abstract method makeDessert() inside. This way all classes that extend this one will need to implement creation of the desserts in their own preferred style and manner.

/* Factory and dessert interfaces */

interface DessertFactory

{

public function makeDessert();

}

interface Dessert

{

public function getType();

}

/* Concrete implementations of the factory and dessert */

class CupCakeFactory implements DessertFactory

{

public function makeDessert()

{

return new CupCake();

}

}

class CupCake implements Dessert

{

public function getType()

{

return 'CupCake';

}

}

/* Client */

$factory = new CupCakeFactory();

$dessert = $factory->makeDessert();

print $dessert->getType();

Factory Pattern:

defines an interface for creating an object, but lets subclasses decide which class to instantiate. Factory Pattern lets a class defer instantiation to subclasses.

As we have seen, Factory enables us to encapsulate instantiation of concrete types, thus enabling us to decide which class to create during runtime. If you want, we can even pass “type” string straight from user input, and the program will create an instance of a class on runtime ( of course, if you input a proper string that the function will understand).

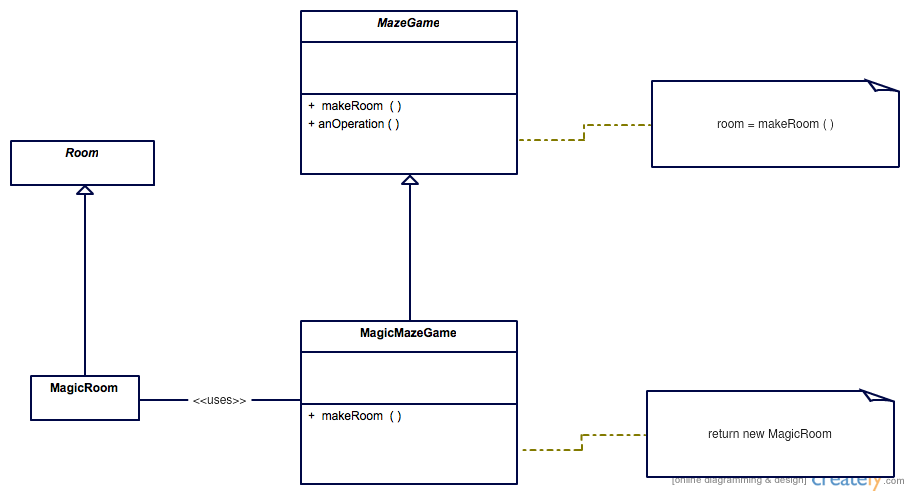

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:New_WikiFactoryMethod.png

# Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factory_method_pattern

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class MazeGame(ABC):

def __init__(self):

self.rooms = []

self._prepare_rooms()

def _prepare_rooms(self):

room1 = self.make_room()

room2 = self.make_room()

room1.connect(room2)

self.rooms.append(room1)

self.rooms.append(room2)

def play(self):

print('Playing using "{}"'.format(self.rooms[0]))

@abstractmethod

def make_room(self):

raise NotImplementedError("You should implement this!")

class MagicMazeGame(MazeGame):

def make_room(self):

return MagicRoom()

class OrdinaryMazeGame(MazeGame):

def make_room(self):

return OrdinaryRoom()

class Room(ABC):

def __init__(self):

self.connected_rooms = []

def connect(self, room):

self.connected_rooms.append(room)

class MagicRoom(Room):

def __str__(self):

return "Magic room"

class OrdinaryRoom(Room):

def __str__(self):

return "Ordinary room"

ordinaryGame = OrdinaryMazeGame()

ordinaryGame.play()

magicGame = MagicMazeGame()

magicGame.play()

Factory Pattern’s primary purpose is to provide a way for users to get an instance with concrete compile-time type, but whose runtime type may be quite different. In other words, a factory that is supposed to return an instance of one class may return an instance of another one, so long both classes inherits same super type. It allows us to change this representation at anytime without affecting the client, as long as the client facing interface doesn’t change.

2 thoughts on “Factory Pattern”